“If you can paint a wall, you can use edge paint.”

Sure, it’s a little more complicated than that, but it’s pretty much the same concept. Edge painting is actually much easier than most people think.

I know you’re eager, but before we jump into the ‘how to’ part of this blog post, I just want to take a moment to talk about why edge paint is as popular as it is, because when I first heard about it my response was: “I will never use that &@#$.” And now, well, I use it.

WHY: EDGE PAINT

Any leather item you make really should have a finished edge of some sort. Turned, burnished, painted, whatever it is, finishing your edges will drastically improve the quality of your work. As I mentioned, when I first heard about edge paint, I really had no intention of using it. Unlike burnishing, which is a process that effects the leather itself (you can read more about that here), edge paint is something that you add to the edge of the leather and then build up by applying multiple layers… just like painting a wall. My logic was, “Why would I finish my edges with something that can peel off, when I could just burnish them.” But, as it turns out, whether or not to use edge point has more to do with the leather you are working with. It’s a situational kind of thing. I’ve been using edge paint for awhile now and I’ve yet to see it peel (although it may over a long period of time, but the effects of burnishing go away with wear as well). Edge paint is also associated with high quality or ‘fine leatherworking', because of the smooth consistent finish it gives.

When: Edge Paint

Like I said, using edge paint is more of a situational decision. As I started working with more kinds of leathers, I realized not all leathers burnish well. Leathers that are thin, supple, and pliable, generally do not burnish well. If the edges happen to be firm enough to create the friction you need to burnish, often those edges will get mashed, especially when using a wooden burnisher. Or, as is usually the case, the edges aren’t firm enough for that to happen. In situations where the edge needs to be exposed, but the leather is too soft to burnish, it’s a really good idea to use edge paint, because with out it, there’s really no good way to get an edge with a consistent finish.

How: Edge Paint

If you’ve burnished an edge before and you’re thinking, ‘I’ll just finish an edge like I normally do, and use edge paint when I normally dye the edge,” don’t think that! Edge painting and burnishing are completely different processes, so it’s best if you forget about burnishing for the time being.

Temporary memory loss applied, let’s begin.

This is a watch strap I was working on. In this picture I've glued both pieces together and evened out the edges with a knife.

1. After you’ve glued your leather together, even out your edges with a knife. I’ll usually just run a knife straight down the edge, blade flat against it. If you have it angled, just be careful that the knife doesn’t bury and cut deeper into the leather than you planned.

Make sure to get your edges as flat as possible in this step, because it’s the last time you’ll be shaping the leather. This is one of the major differences with burnishing, there is no sanding the leather to even out edges.

First coat of paint applied... just waiting awhile for it to dry.

It’s okay to sand edges when burnishing because you will also bevel your edges with an edge beveler. When you sand, the gain (topside) of the leather with start to fold over, and beveling removes that folded over part. But, when you’re working with thin leathers, you generally can’t bevel. There’s not enough leather to bevel, you’ll just cut the entire way through it. Long story short, don’t sand, don’t bevel, just even out the edges with a knife.

First coat once it has dried. You can see the fibers and uneven parts through the layer of paint.

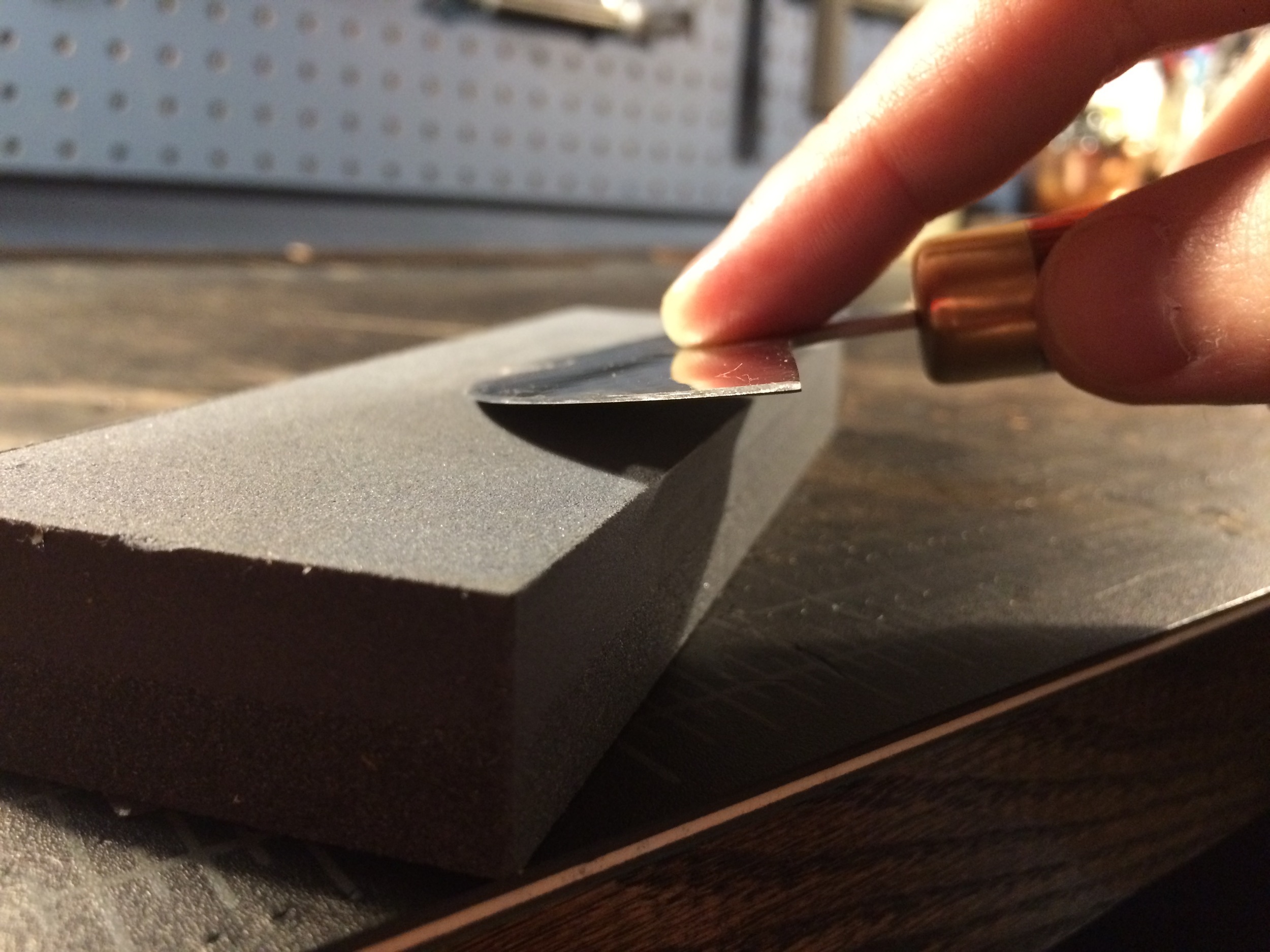

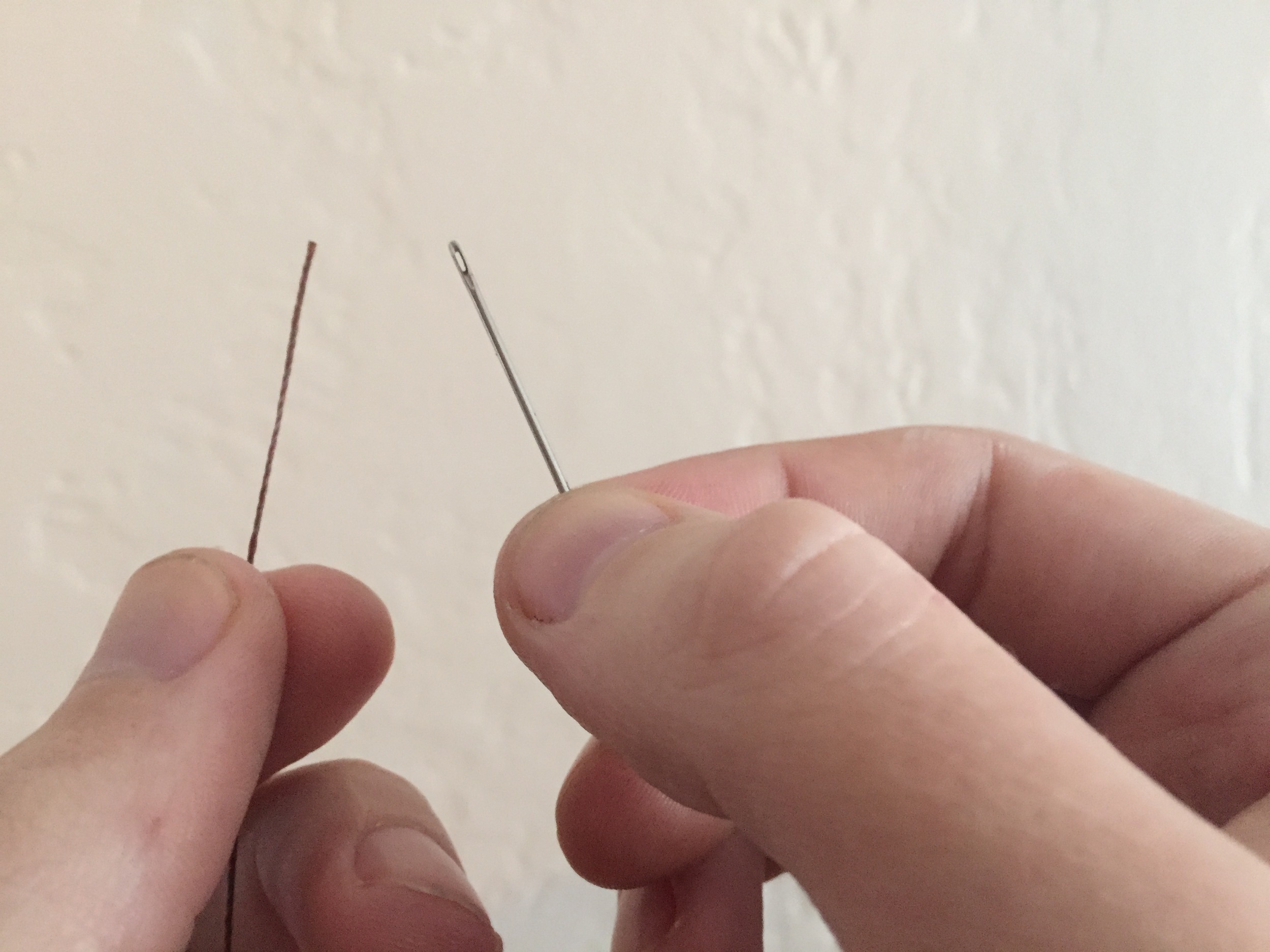

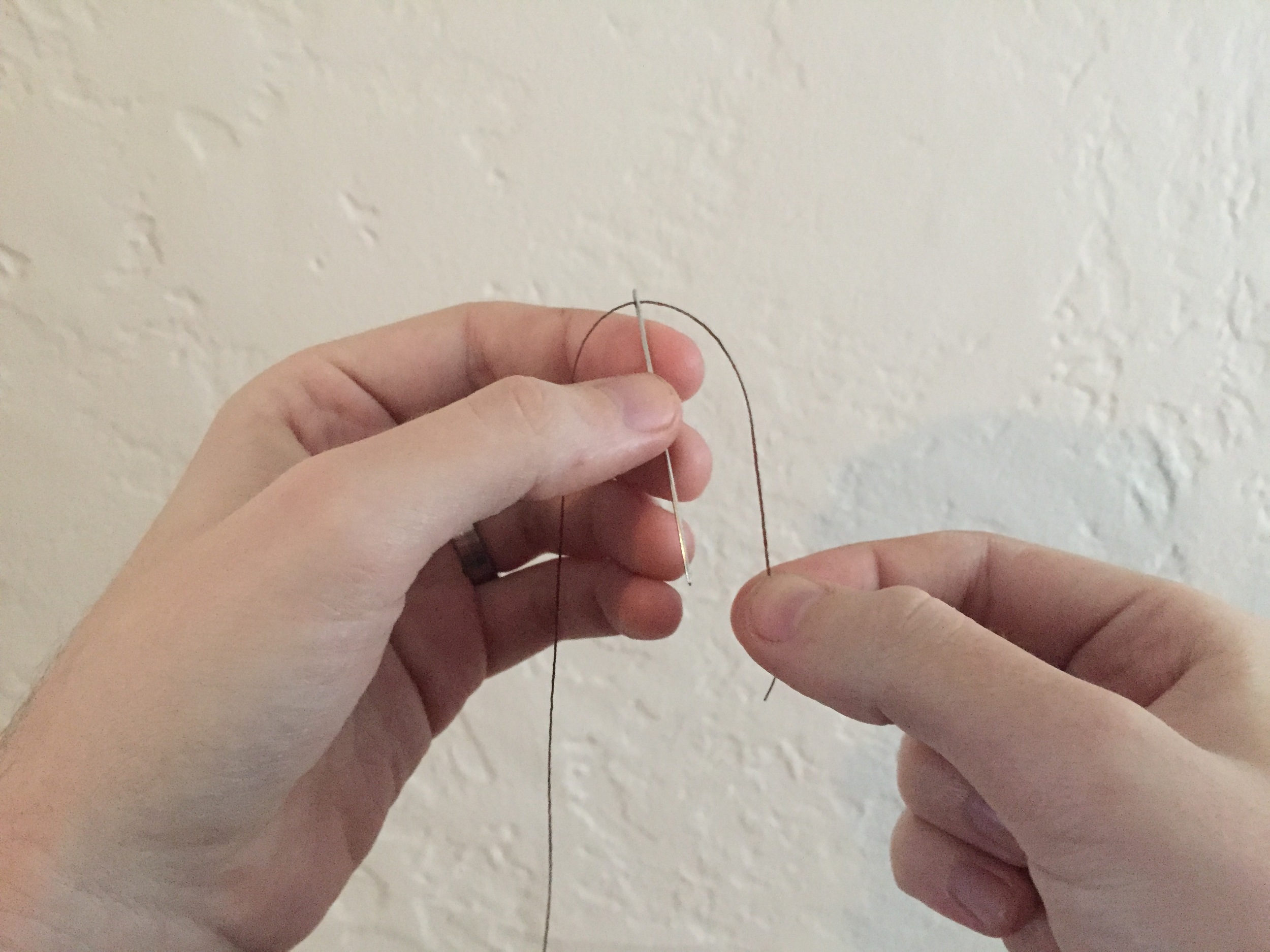

2. After you’ve done that, apply the edge paint to the edge. Applying edge paint can be a little tricky because you absolutely have to keep it on the edge. If it spills over the edge, unto the leather, it will stain the leather. For that reason I use this tool. Make sure to apply a nice even and smooth coat. If you see the paint has pooled in one area, make sure to spread it out.

3. Allow 10 minutes (at least) for the paint to dry. Depending on the paint your using, it may be longer. You can generally tell by looking, but don’t rush this part because it will ruin your edges if you move on before allowing it to dry. As an impatient person, I’m talking from experience.

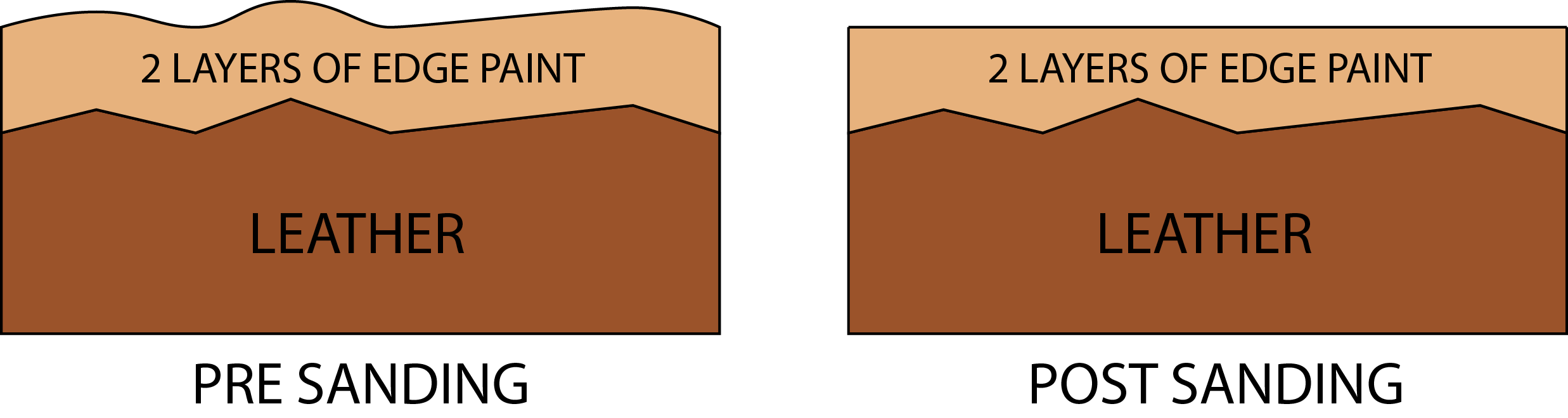

4. Next is where sanding comes in. Like I said, at this point, there is no more shaping of the leather itself, so you’ll only be sanding the layer of paint you’ve applied. Hit it lightly with 800 grit sand paper. This is just to help the second layer you are about to apply adhere to the previous layer.

This is my first two layers just after sanding. You can see a few inconsistencies. The one in the middle and the one on the right were caused by not waiting long enough for the paint to dry. The one on the left however, was from not enough paint. I should've applied another coat and evened it out again, but I did not and you will see the mistake in my final product.

5. After you’ve applied a second layer and allowed it to dry it’s time to sand again, but this time with a different purpose. This, in my opinion, is the most important step in getting nice edges using edge paint. If you look at your edge up to this point, you’ll still see the imperfections that were in the edge of the leather in the edge paint (i.e. the crease where the two pieces of leather meet, loose grain, etc.). Now’s the time to get rid of those, otherwise it’s going to take an absurd amount of coats until it smooths out. I hit the edges with 600 grit sand paper, and sand the paint until it is flat and all the previous mentioned imperfections can no longer be seen. Again, you’re not sanding until you hit the leather, you’re just sanding the paint you’ve built up to even it off.

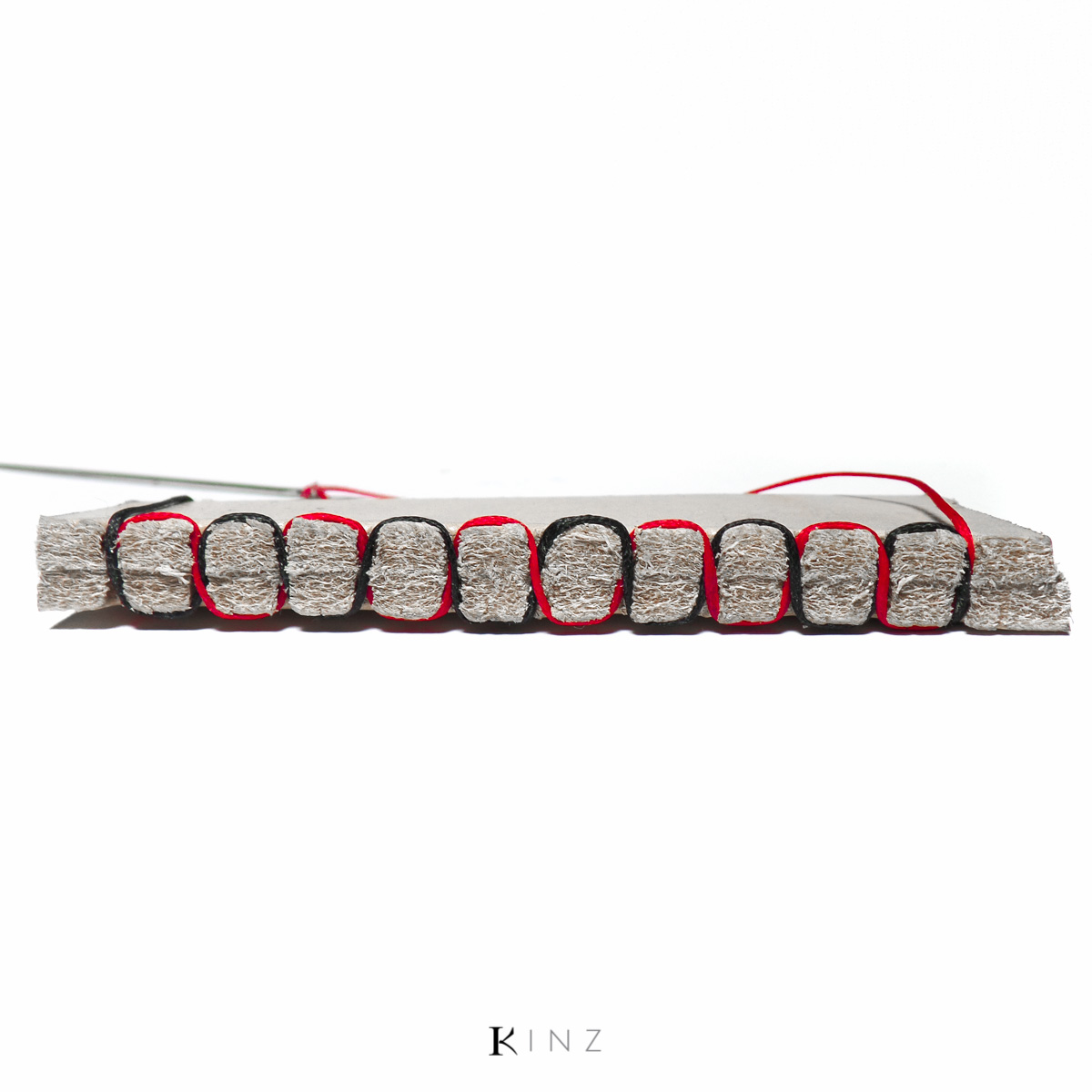

This is the final product after a few final coats, hitting lightly with 800 grit sandpaper, and then buffing with a piece of canvas. As I mentioned earlier, you can see my mistake on the very end, but other than that I'm pretty happy with how it turned out.

6. Finally, I will usually do 2-3 more coats depending on how much I had to sand off. I make sure to add enough until the edge looks rounded instead of flat. After the final coat is done drying, I'll hit it lightly with 800 grit sand paper, and then buff it with a piece of canvas.

What: Edge Paint

The edge paint I use is called Vernis Edge Paint.

Who: Edge Paint

So, I really want to see what your projects look like finished with edge paint. If you’d like to share what your working on please follow me on Instagram @goldbarkleather, and tag your photo with #goldbarkbrag. That way, I get to see what you’re making, and I’ll feature it if it’s some of the best of your work!